Latest Blogs

-

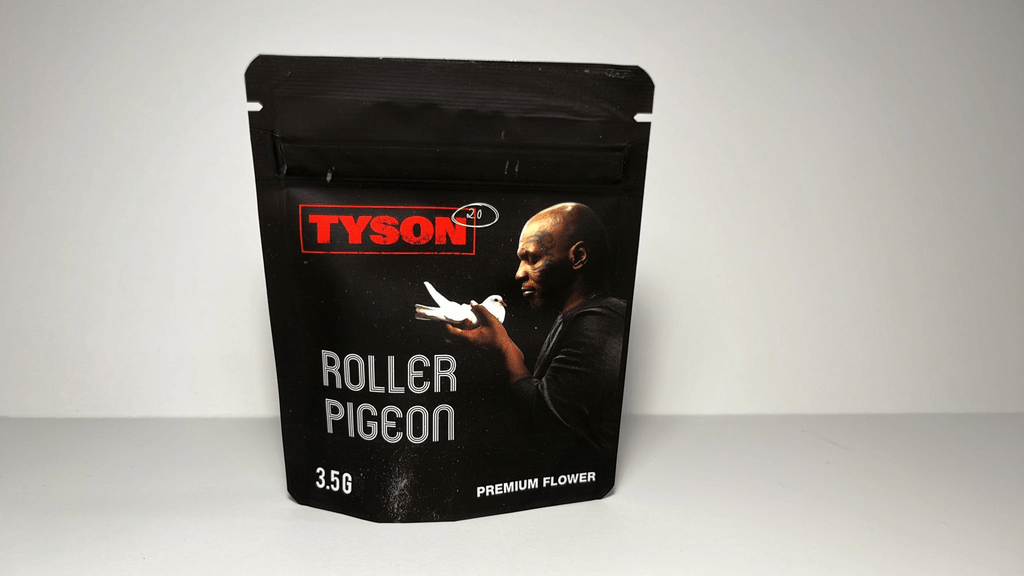

The Flavor of Fame: Pop Culture’s Secret Sauce in Strain Success

Pop culture hasn’t just reflected cannabis—it has rewired how strains are named, discovered, and sold. From hip-hop to NBA crossovers to stoner comedies, entertainment turned cultivar names into brands, and…

-

In-Person Only? The Truth Behind Delivery-Exclusive Cannabis Products

When it comes to scoring exclusive cannabis products, one question often arises: are these specialty items available via delivery, or only in-store? The answer: in most cases, exclusives remain in-store…

-

From Dabs to Doorbusters: The Best Limited Drops on Cannabis’ Big Three Holidays

On 4/20, retailers treat the day like cannabis’ Black Friday, stacking deep promotions, limited drops, and bundle deals. The data backs the hype: Headset tracked $83.6 million in sales across…